In Memoriam: Isidore Starr (1911-2018)

In Memoriam: Isidore Starr (1911-2018)

- TSSP Newsletter

- In Memoriam: Isidore Starr (1911-2018)

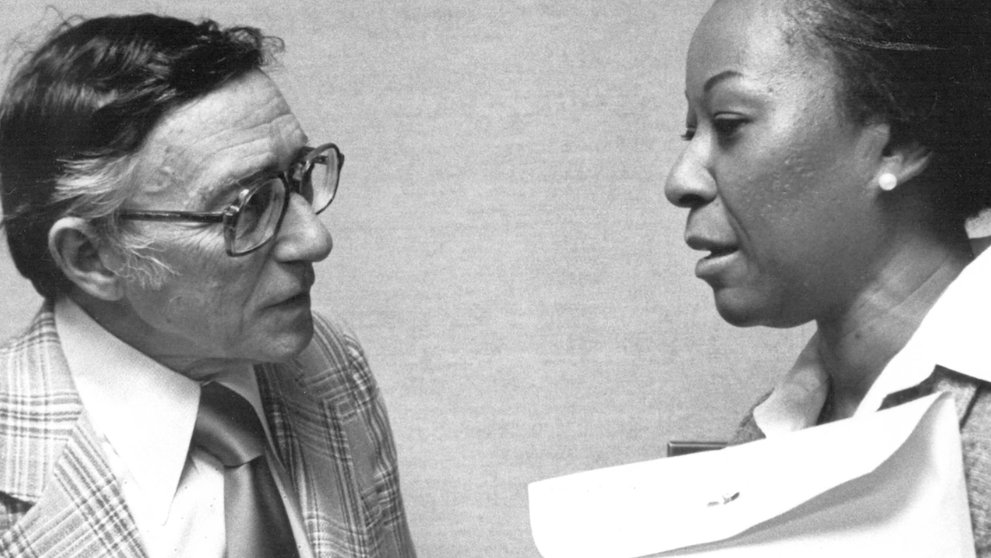

Isidore Starr, President of National Council for the Social Studies in 1964, considered by many to be “the father of law-related education,” passed away on February 10, 2018, at the age of 106.

A Son of Immigrants

Isidore was born in Brooklyn, New York on November 24, 1911. His parents had fled Russia to escape the tyranny of the Czar. The Starrs raised four children in a “railroad apartment” (a narrow hallway runs the length of the building connected the rooms) on Rockaway Avenue. Isidore remembers speaking Yiddish until he started kindergarten, at which time he slowly picked up English words and soon became fluent.

In a 2012 interview with Anna Samuels of the Legacy Project for the State of Washington, Isidore recalled reading in high school an 1899 essay by William James, “On a Certain Blindness in Human Beings,” which discusses the role emotions play in the forming of opinions. The dedication of his English teacher, Ms. Harrington, to introducing advanced texts and discussion topics to a class of 16-year-olds surely influenced Isidore’s idea of what it means to be an effective instructor.

Besting a “Deadly” Boring Curriculum

While he attended the City College of New York, the stock market crashed. “I remember my mother gave me 50 cents to go to college, 5 cents for the subway each way, and 5 cents to buy an apple.” In 1933, he headed to St. John’s University School of Law, and soon began teaching civics at Brooklyn Technical High School. At 23 years old, he wasn’t much older than the 6,000 rambunctious teenage boys he had as students. He quickly realized that the curriculum was to blame for students’ lack of interest in history. The standard lesson plans comprised rote memorization exercises. “It was deadly!” Isidore remembered. “I had been trained in the philosophy of John Dewey, which meant including students in the learning process, in other words, learning consisted of teacher and student learning together, not the teacher questioning the student.”

Isidore’s first inquiry lesson dealt with the topic of police brutality: when, if ever, were police justified in using torture to elicit information from suspects? After receiving such a positive response to his first law-focused lesson, Isidore began to introduce the law into lessons whenever possible. Over the ensuing decades, he developed his teaching program to encompass a Bill of Rights education course in conjunction with the Civil Liberties Education Foundation and the National Council of the Social Studies, serving on the NCSS board in 1951.

World War and Post-war Hysteria

Isidore pursued a Master’s degree in History at Columbia University, enrolled at the Brooklyn Law School of St. Lawrence University, and married Kay Rueben in 1940. Two years later, Isidore was drafted, becoming an Information Education Officer shortly before being shipped to the Philippines, where he organized language lessons in Japanese and Tagalog for his shipmates.

After the war and back as a teacher at Brooklyn Tech, Isidore’s classroom techniques began to be noticed, in part due to the Red Scare of the 1950s. Teachers were in constant fear of losing their jobs. In 1951 he was called down to the principal’s office and “accused” of teaching, “the Declaration of Independence [is] a collection of glittering generalities.” Isidore responded, “What’s wrong with that?” He explained that in teaching the Declaration, he presented his class with a variety of definitions: the document is 1) a collection of “glittering generalities,” which was taken directly from Rise of American Civilization, a popular text book at the time; 2) the birth certificate of the American nation; or 3) a war song. In conclusion, he would ask his students if they had a better definition. The principal, who actually supported Isidore’s theory of teaching, found little to counter that explanation.

Lessons in the Law

In 1961, when Queen’s College in New York City was looking for a dynamic teacher “to step in for a year,” they hired Isidore Starr. He was a much beloved teacher there until 1975. It was during this time that Isidore wrote an article, “Teaching Controversial Issues Through Supreme Court Decisions” for the NCSS flagship journal Social Education, suggesting “that if a Supreme Court can handle controversial issues in an intelligent and civil way, why shouldn’t we be able to do this in classes?” The title, which the editor of Social Education identified as “too controversial,” was changed to “Recent Supreme Court Decisions”—and that became the heading for his recurrent columns. From 1961 to 1963, Isidore wrote a series of articles for Social Education, which were later compiled and published in a book, The Supreme Court and Contemporary Issues (Encyclopaedia Britannica Educational Corp, 1969). The popularity of his writing led to his being elected President of NCSS in 1964.

After “retiring” with his wife to Arizona, Isidore taught law courses the next 13 summers, led seminars in various locations, including Texas and Hawaii, and made many close friends. When some years later Kay developed dementia, the two moved to Seattle to be closer to their son Larry and his family. When, in 2008, Kay died as a result of an accident on the part of the nursing home staff, Isidore was ready to defend her case (which ended in mediation). “I wanted very much to go to trial, because I wanted to address the jury to get some publicity for people who are old,” he explains. “I was told by every lawyer I knew that suing was a hopeless task, that a 97-year-old person wasn’t worth anything. I was going to prove that a 97-year-old person was worth as much as a young person.”

Accolades from Educators and Scholars

NCSS President Terry Cherry said, “At our NCSS Annual Conference in Seattle in 2012, the officers and Board of Directors were proud to present Dr. Starr with an award at the House of Delegates, recognizing his contributions to our profession and our country.”

NCSS President Terry Cherry said, “At our NCSS Annual Conference in Seattle in 2012, the officers and Board of Directors were proud to present Dr. Starr with an award at the House of Delegates, recognizing his contributions to our profession and our country.”

NCSS Executive Director Lawrence M. Paska stated, “As he approached the peak of his professional career, Isidore Starr chose to publish his best work in Social Education, advocating for critical thinking in social studies classrooms. In our own era, we continue to be guided by the foundation he built for civics and law-related education in the social studies.”

StreetLaw Executive Director Lee Arbetman recommended the wonderful 16-minute documentary (mentioned earlier), “Isidore Starr: Leading a Revolution in Civics,” which was produced by the Centre for Education, Law and Society at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. It premiered in 2015 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the American Bar Association's National Law-related Education Conference, to a standing ovation.

Ronald W. Evans, author of The Social Studies Wars and Professor in the School of Teacher Education at San Diego State University, pointed to Isidore’s own reflections, “The Law Studies Movement: A Memoir,” published in 1977 in the Peabody Journal of Education, and reminds us that Starr’s collected papers are preserved at the University of Washington. Evans remarks, "Isidore Starr was a champion of a Deweyan, issues-centered approach to education. A fighter to the end, he rightfully deserves an honored place in the pantheon of contributors to the social studies field.”

In 2011, the year of Isidore’s 100th birthday, The Seattle University School of Law held a conference in his honor, inviting more than 80 educators, speakers, and politicians involved in the creation and proliferation of the law-studies movement to present.

“Education to me is a slow, laborious process, which in a sense holds the key to the future,” said Isidore Starr in the Legacy Project interview. “We have to be tolerant of each other, accept each other, weigh each other’s arguments, and argue without killing each other or without destroying each other. . . . People have to be educated that humanity is a many-splendored thing, many colors and many views, many opinions, many ideas.”